Given its central importance in the history of science, it is perhaps surprising that Aristotle’s School, the Lyceum or Peripatos, did not thrive as a discrete institution for long after the death of its founder in 322 BC. The ancient biographical sources – of whom the third century AD biographer Diogenes Laertius is probably the most important – record a succession of Scholarchs of the Lyceum which all but dies out at the beginning of the second century BC. When Sulla took Athens in 86 BC, and had the Aristotelian library brought back to Rome (after it had languished out of sight for over a century), the fate of the Lyceum in its original form had been sealed. This is not to say that Aristotelians were not still active well into our era; simply that we know next to nothing of their activities. Of the Peripatetics of his own day (in the early first century BC), Cicero remarked that they were «as if born of themselves, with no knowledge of the doctrines of their founder».

Fundamental problems of evidence mean that this article inevitably focuses on the scientific work of two important early members of Aristotle’s School of whom we do know something, Theophrastus of Eresus (ca. 371-287 BC) and Strato of Lampsacus (fl. mid third century BC). Theophrastus will inevitably take more of our time; he is the only early Head of the Lyceum – the only early out-and-out Peripatetic for that matter – whose works are not lost. We only know of Strato through the indirect and unreliable testimony of later sources, and he is included as something of a test case.

There follows a brief survey of the character of subsequent Peripatetic work in natural science, and an assessment of the importance of the Lyceum and its doctrines in the development of other philosophical systems. A host of important matters will necessarily be passed over or mentioned only briefly. The history of the Lyceum as an institution is dealt with in detail elsewhere in this volume, as is the medical work of doctors with Aristotelian connections, the research in harmonics of Aristoxenus of Tarentum (b. 370 BC, who is generally, if problematically, regarded as an Aristotelian). Peripatetic influence on the research methods and establishment of the Museum at Alexandria, the role of the early Aristotelians in the establishment of the doxographical tradition, and the work of the later commentators on Aristotle are similarly discussed elsewhere. Even so, something by way of background will be necessary here if the complex relationships of later Aristotelians to their founder is to be understood.

The conventional history of Aristotle’s own career and the early history of his school may be dealt with quickly. A Stagirite with connections to the ruling factions in Macedonia, working in Athens at a time when Athenians were deeply suspicious of powerful Northerners, Aristotle is portrayed by most of our biographical sources as something of an outsider in his own lifetime. Even during his years as a pupil of Plato at the Academy this seems to have been the case, and in due course, we are told, he rebelled. «Like a colt rejecting its mother», says Diogenes Laertius, almost certainly drawing on a much earlier and probably reputable source, Aristotle spurned Plato while he was still alive. Scholars like to personalize the split with Plato’s School. Perhaps Aristotle was disappointed, some say, at the elevation of Plato’s cousin Speusippus (407–339) to the position of Scholarch of the Academy on the death of Plato. It is just as likely that his own philosophical work, particularly in natural science where he all but discarded the theory of Forms, put an intolerable strain on his Platonic affiliations. The son of a doctor, Aristotle’s own inclinations may well have taken him in the direction of natural science, something Plato’s philosophy had not given the attention Aristotle thought it deserved.

It may be unfair to single out Plato for criticism here; in a famous passage in Book I of De partibus animalium, Aristotle refers to the prejudice evinced by most philosophers against the study of natural subjects which appear less noble than the traditionally higher objects of study. He relates with approval the story of Heraclitus, disturbed on the toilet by some friends. «Do not be embarrassed», he is supposed to have said to them, «but enter, for there are gods even here». Whatever the case, Aristotle left Athens and the Academy, and spent the years 348–345 at first at Assos in the Troad and then at Mytilene on Lesbos. After a subsequent period at the Macedonian court (where he may or may not have worked as tutor to the young Alexander), and a brief return to his home city of Stagira, he went back to Athens in 335 BC. On finding Xenocrates recently installed as Head of the Academy, he resolved, we are told, to found his own institution.

Like Plato, Aristotle focused his activity on his return in a congenial suburban area of Athens; he chose a grove sacred to Apollo ‘Lyceius’, a place frequented by young gymnasts and already well-known as a haunt of sophists and philosophers. The area favoured by Aristotle is mentioned by the comic poet Aristophanes as a place for taking walks, and the most common ancient name given Aristotelian philosophers, ‘peripatetic’, simply means ‘walking about’. At first the Lyceum was a loosely organized secular institution with no legal status. In spite of the place’s association with Apollo, the Lyceum was not initially, it seems, a thíasos, enjoying an official association with the cult of Apollo. Aristotle probably leased his land, and perhaps a building near the sacred precinct. This almost certainly changed under the subsequent headship of Theophrastus. As a resident alien, a metic, in Athens, Aristotle was not allowed to own any property, although his Athenian associates certainly would have had this right, and by the time of Theophrastus’ death, the Lyceum did own property, for its use is discussed in Theophrastus’ will, preserved by Diogenes Laertius.

The Lyceum’s early success must have been considerable; an anonymous ancient commentator on Demosthenes includes it in his list of the three great gymnásia in early fourth century Athens (the others being the Academy of Plato, and the Cynosarges, a rather different kind of establishment used by those who were not Athenian). Aristotle stayed there, says Diogenes, for thirteen years.

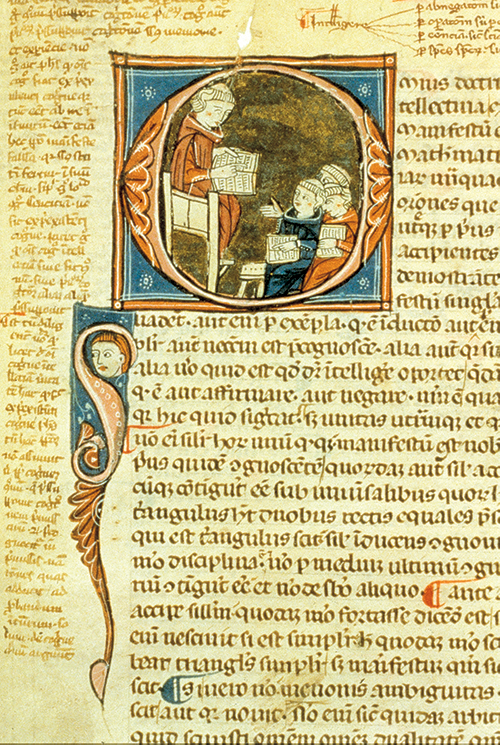

The business of the Lyceum seems to have been divided between the offering of public lectures on general matters of philosophical interest (for which fees were probably charged), and the discussion of detailed problems amongst much smaller groups. One of the striking things about the corpus of Aristotelian writings – especially the so-called ‘school treatises’ written as lecture notes for advanced students and colleagues – is their character as work in progress. Of course, in the series of treatises known as the Organon, Aristotle had examined, and done so with some authority, basic problems surrounding language, logic and the ways in which we can speak about things clearly and unambiguously. But a primary function of Aristotelian logic and epistemology was to help the student of nature sift through the mass of phenomenal material presented to us by the world, and it was here that Aristotle ultimately spent much of his time. Where Plato had approached his study of the terrestrial environment in the Timaeus from the position that what surrounds us in the physical world is an imperfect copy of a perfect, insubstantial original, Aristotle insisted that the proper study of nature should begin with the collection of the widest possible variety of particular phenomena relating to the matter under investigation, and proceed through a stage of hypothesis and characterization to the point where ideas could be tested with the machinery of syllogistic logic. The invention of syllogistic logic is something especially associated with Aristotle in antiquity; its development became a central concern of the Stoics, who thus secured themselves a place in the history of the broader Aristotelian tradition.

This, of course, is not only a considerable simplification of Aristotelian method; as a characterization, I should point out that it is not universally accepted by modern scholars, even at this level of generality. While it seems to most modern critics that Aristotelian treatises like Historia animalium may reasonably be read as examples of the first stage of an investigation involving the collection of differences, and their preliminary arrangement as a prelude to the detailed examination of causes, others insist that nearly all Aristotelian natural science was intended to be a proving ground for the techniques of logical scientific demonstration. That is to say, in its more extreme form, that treatises like the Historia animalium are, in a sense, workbooks for the student of syllogistic logic. This is a view not shared by the present writer, and not confirmed, in his opinion, by the subsequent history of Aristotelian scientific method.

If certain details of the relations between Aristotelian theory and practice are hotly debated today – and the question is a highly important one, given that around a quarter of the surviving Aristotelian writings are concerned in some way with biology – this cannot detain us here for long. The next two sections of this article involve an examination of the interactions with Aristotelian method and doctrine exhibited in the work of the two men who headed the Lyceum in the generations immediately after Aristotle. Theophrastus of Eresus, and to a lesser extent his successor as Head of the School, Strato of Lampsacus, pursued research into natural science following the broad methodological directions set out by Aristotle himself, with results that are not only of interest in themselves, but which also cast some light on the subsequent fate of the Lyceum as an institution.

Even in antiquity, Theophrastus of Eresus (a small city in the south of Lesbos) was regarded as the most distinguished member of the Lyceum after the death of its founder. He was certainly the best known. The ancient biographers record that his name was originally Tyrtamos, but that Aristotle gave him the name ‘Theophrastus’ (which could either mean «gifted with divine speech», or «marked out by god») because of the quality of his literary style. Whether or not this is true (let alone justified), it seems that he did attract huge audiences to his lectures in the Aristotelian School, enriched it materially, and at the same time was able to continue his master’s studies in a very wide range of fields. His two major botanical works, De causis plantarum, and Historia plantarum constitute the most extensive ancient treatments of their subject to have survived; it is arguable that they were the most extensive to have been composed in early antiquity. A number of shorter works are also preserved under Theophrastus’ name. The list includes essays with titles like On giddiness, On lassitude, On sweat, On winds, On the signs of storms, On water, On fish that live on dry land. Few of his ethical and political works survive; most important of these is the Characters, vignettes of human stereotypes which show a close affinity with the characters presented in the plays of the comic poet Menander, who is supposed by some ancient witnesses to have been a pupil of Theophrastus. These small works – sometimes called the opuscula – have attracted some suspicion over the years. Their small scale and abbreviated character has led some modern authorities to condemn them as fragments of larger works which do not survive. This view is not widely held today.

According to Diogenes Laertius, Theophrastus began his study of philosophy in Eresus, but then moved to Athens and heard Plato lecture for a time before transferring his allegiance to Aristotle. It is likely that the two spent time together in Assos, in the Troad. (Aristotle, as we have already noted, spent the years 348-345 there, after the death of Plato, and it is widely believed that both men developed their characteristic interest in the close practical study of biological and zoological phenomena while they were there.) His scientific work is most conveniently approached through his own guide to the subject – the methodological excursus on the study of nature known as the Metaphysics. The work is concerned with general problems relating to the types of knowledge we can hope to have about the universe and constitutes an important early reaction to the epistemological work of both the Academy and the Lyceum.

For the most part, Theophrastus’ Metaphysics follows Aristotle very closely – even though Aristotle himself is nowhere named, and even though the language Theophrastus employs in the description of Aristotelian concepts is not always Aristotle’s own – and much of the work seems to be taken up with a thinly disguised polemic against Plato, or more accurately, the leading minds in the Academy in the generation after Plato’s. Where, asks Theophrastus at the beginning of the work, should one draw the line between the study of first principles and the study of nature. Plato had of course drawn a clear enough line, arguing that reality does not inhere in the objects of sense perception, but only in the perfect «Forms» which can properly be approached and comprehended only through the careful exercise of reason. Plato and his followers had used geometry as an important tool in ascending to the study of the Forms; in a famous passage in the Republic, Socrates had told Glaucon that the Guardians of the ideal state should study, among other things, astronomy – but only if they «set aside the things in the heavens» in their deliberations. Plato, in the Timaeus (a dialogue to which Theophrastus refers explicitly in the Metaphysics) argued that the phenomenal world, made up as it is of disordered and unstable matter, is not the proper focus for the philosopher’s attention – even though the philosopher might wish quite reasonably to turn his mind to the explication of natural phenomena as an enjoyable pastime.

Theophrastus makes it clear that he too accepts that the works of Nature are «more disordered» than the objects of «higher» study – but they are also richer, more bounteous and interesting in their own right. He poses some difficult questions for those who take the hard line view that there is an unbridgeable gap between the works of perfection and the works of Nature. He insists that the Universe is not a series of discrete ‘episodes’, but rather a set of hierarchies with some things superior and others inferior. Theophrastus here, as often, seems to be inviting us to see an analogy between the political organization of the human and animal worlds, and the universe as a whole.

If one accepts this broad view of the universe, he continues, then what does in fact stand in the most honourable position? Mathematical objects? Some Platonists took this view, he says. But Theophrastus finds it difficult to connect numbers and ratios with the physical objects of our sense perception. In particular, he cannot see how they can be the substrate of life and movement. In the end, he throws himself more or less firmly behind Aristotle; but it is the Aristotle of the biological treatises who seems to be most in his mind. And one of the underlying themes of the Metaphysics is one which Aristotle only hints at in a few of the most difficult parts of his zoological work. Theophrastus insists that we must limit our demands for explanation; if we do not, then we risk destroying explanation altogether. Take the case, he suggests, of Aristotle’s ‘Unmoved Mover’, the supposed source of all movement in the Universe. Aristotle had argued that this entity in some way caused the near perfect circular motion of the stars. This circular motion, characteristic of objects in the supra-lunary sphere, in turn imparts movement of an altogether different, an inferior kind, to physical objects nearer the Earth, in the sub-lunary sphere. But if all that happens in the world, happens to some end which is good, then what is the purpose of the circular motion of the stars?, asks Theophrastus. It might be reasonable to think that the teleological impulse towards what is best should – as Plato certainly thought – involve the emulation of some kind of model. If what is ultimately best induces what is best in other things, then we should expect the heavenly bodies to stand still like the Unmoved Mover – unless, that is, something stops them from being better than they might be. But Theophrastus very significantly does not pursue this question at all; he simply says that it is, as it were, an unjustifiable luxury. The person who seeks order throughout the Universe is, he says, an undiscriminating one.

It is a theme which is developed in a slightly different context at the end of the work, when Theophrastus comes to defend teleology against its own unreasonably hard-line proponents who demand, in effect, that if something does not exhibit signs of purpose-directed activity, then it should not be studied at all. Following Aristotle very closely here, he insists that difficult cases for the teleologist – the purpose of breasts in men, the tides of the sea or changes in sea level over time, the existence of horns in animals, like deer, where they are a hindrance, the growth of the beard in men and so on – do not invalidate the whole programme of teleological investigation into nature, but simply show us that where matter predominates over form, there will inevitably be unpredictable results (Aristotle had covered a certain amount of this ground himself, in the last book of his work De generatione animalium). Matter predominates over form in many of the areas of investigation into Nature which Theophrastus found especially interesting. Indeed, it is difficult to find final causes for all things – yet «all things» are exactly what interested Theophrastus, and his own natural science, far from retreating into an epistemological straight-jacket, exhibits a clear and typically Aristotelian sense of wonder and enthusiasm for the variety he found around him.

He often appears cautious and undogmatic – a characteristic which has received much attention from scholars in recent years. At the beginning of the short work On stones, for instance, he offers several possible accounts of the generation of mineral substances in the earth without seeming explicitly to favour any particular set of details. And in the body of his text, there seems to be no serious attempt at taxonomy at all; something difficult to grasp for those brought up in the modern traditions of botany or mineralogy. He is mainly interested in compiling a handlist of unusual and useful substances which can be had from the earth, without really locating them in any strict taxonomical or theoretical framework at all. What often appears to us as caution, then, when Theophrastus offers several accounts for the origin of some substance or prefaces his observations about something with the word «perhaps ...», can just as easily be a function of his own epistemologically founded belief that certainty is not always on offer. And this, paradoxically enough, was a view he shared with the Plato of the Timaeus; yet he stands apart from Plato in the seriousness of his commitment to the study of these phenomena which show little promise of revealing signs of order.

The case is similar with the treatise On fire. Considering fire’s manifestations around us, Theophrastus asks whether we are really correct when we call it an element. In the company of many of his predecessors, Aristotle had thought fire to be elemental, but Theophrastus argued that something which can only exist in the company of a material substrate – and which can apparently be generated – cannot be called an element in the same sense as earth, air and water. Of all the simple substances, fire has the most special powers, he observes at the beginning of the work. The rest of his time is spent collecting interesting, useful and sometimes unusual instances of phenomena involving fire — the anti-taxonomical principle at stake being broadly similar to that employed in On stones. The opening of the On fire is worth quoting for its attention to inconvenient detail:

Of the simple substances, fire possesses the most distinctive faculties. For air, and water and earth can only change into one another and none of them is generative of itself. Fire on the other hand is naturally able to generate and destroy itself. The smaller generates the larger and the larger destroys the smaller. Moreover, in most cases fire is generated by a kind of force; by striking hard objects, like stones, by friction and compression as happens with firesticks and by all things which possess movement, like those which are ignited and melted. (Clouds are gathered and compressed out of air itself. Their motions cause firewinds and thunderbolts). [...] Fire is also generated in the other ways we have observed, be they above the earth, on the earth or beneath it. Most of these seem to come about as a result of violence. (De igne, I)

Theophrastus avoids drawing any firm conclusions about fire’s status as an element, nor does he disagree explicitly with what Aristotle had said; he seems mainly concerned with collecting all the relevant phenomena. So it is again with the very short work On odours; Theophrastus’ subject here is not so much the physiological basis of smell and taste, or the taxonomy of odours, as a concern with the types of substances which produce fragrances useful or striking to man.

Where certain explananda lack a final cause, then, Theophrastus does not pass them over. More than Aristotle perhaps, Theophrastus seems to regard certain phenomena as worthy of study because of their utility or interest to man. Aristotle had drawn a distinction between two types of final cause, in the Physics (II, 2), between the goal of something’s existence being to service something outside the organism exhibiting the goal-directed activity, and the impulse which directs the organism itself towards being as good as it possibly can be as an ideal example of its type. The first of these goals is sometimes described as ‘anthropocentric’ and it was used both by Aristotle and Theophrastus to explain phenomena which do not in themselves seem to occur for any purpose, but which are nonetheless useful to man. Rainfall is Aristotle’s best known case. Theophrastus seems to have developed this method of teleological thinking to justify his selection of a great many phenomena which occur in what were traditionally the lowest levels of the hierarchy of nature. There is even a case for suggesting that Theophrastus saw some kind of teleological force at work in making something the object of human interest and curiosity.

Now to the botanical works. By their very titles, we are invited to compare the De causis plantarum, and the Historia plantarum, with the De partibus animalium, and Historia animalium of Aristotle. In the case of Aristotle, to put it very simply indeed, the Historia animalium collects the data about a wide range of creatures, organized loosely in accordance with preliminary categories based on the differences of their parts; the De partibus animalium proceeds to investigate the causes for animals being the way they are. Theophrastus Historia plantarum opens in a very Aristotelian vein: the first step in the study of plants to collect their ‘differences’ as a prelude to the examination of their causes. Many modern translations render the Greek word diaphoraí with some phrase including the word ‘classification’, as if collecting the differences inevitably involves some kind of theoretical process of differentiation. Yet it is far from clear that this – if what we mean by classification is the kind of botanical taxonomy we are used to in modern science – is what Theophrastus has in mind in any of his botanical works. Certainly, he does not end up offering us a detailed classification of plants; rather a list of cases which require further analysis.

In considering the distinctive characters of plants and their nature generally, one must take into account their parts, their qualities, the ways in which their life originates, and the course which it follows in each case: (conduct and activities we do not find in them, as we do in animals). Now the differences in the way in which their life originates, in their qualities and in their life-history are comparatively easy to observe and are simpler, while those shown in their ‘parts’ present more complexity. Indeed it has not even been satisfactorily determined what ought and what ought not to be called ‘parts’ and some difficulty is involved in making the distinction. (Historia plantarum, I, 1, 1)

The aporetic, problematizing tone of this introductory passage is typical of what we have already seen of Theophrastus’ scientific temper. We are prepared, after reading Theophrastus’ warnings in the Metaphysics about pushing the demand for explanation too far, for the following passage, which suggests that we should not expect plants to exhibit order in quite the same way as animals:

And in general, as we have said, we must not assume that in all respects there is complete correspondence between plants and animals. And that is why the number also of parts is indeterminate; for a plant has the power of growth in all its parts, inasmuch as it has life in all its parts. Wherefore we should suppose the case to be as I have said, not only in regard to the matters now before us, but in view also of those which will come before us presently; for it is waste of time to take great pains to make comparisons where that is impossible, and in so doing we may lose sight also of our proper subject of enquiry. The enquiry into plants, to put it generally, may either take account of the external parts and the form of the plant generally, or else of their internal parts: the latter method corresponds to the study of animals by dissection. Further we must consider which parts belong to all plants alike, which are peculiar to some one kind, and which of those which belong to all alike are themselves alike in all cases; for instance, leaves, roots, bark. And again, if in some cases analogy ought to be considered (for instance, an analogy presented by animals), we must keep this also in view; and in that case we must of course make the closest resemblances and the most perfectly developed examples our standard; and, finally, the ways in which the parts of plants are affected must be compared to the corresponding effects in the case of animals, so far as one can in any given case find an analogy for comparison. (ibidem, 4)

The first five chapters of Book I of the Historia plantarum are taken up with a discussion of the problem of deciding which differences are worth noting; which botanical phenomena are likely to prove the rewarding focus of further investigation. He groups all plants into three broad forms which he calls tree, shrub, ‘undershrub’ and herb. A tree, he says, is something which grows from its root with a single stem, with knots and branches. It is not easily uprooted. A shrub grows from its root with many branches, like bramble, while an undershrub grows from its root with many stems as well as branches. A herb is a plant which grows leaves straight from its roots, without any main stem. Typically, Theophrastus immediately qualifies this outline, saying that we should only expect these categories to hold in general terms; there are, he says, certain exceptions, and overlaps to these basic types. Exact order in this matter is not to be found, he warns.

Theophrastus proceeds to examine a variety of differences which could conceivably aid us in the organization of the huge amount of botanical data we face in the world, but continually reaches the same conclusions; indeterminate factors in the growth and management of plants, resulting from external factors such as climate and environment, or man-made like cultivation, not to mention the innate variety in individual plants, make it possible to organize the subject only in general terms.

The remainder of the Book I is taken up with a survey of typical examples of the four basic classes mentioned above, and their parts – flowers, fruits, and the extent to which they vary because of their environment. The last part of the book considers in general terms the important differences of trees, flowers, and fruits. Book II considers the propagation of plants; a subject of great difficulty for someone brought up with the idea that analogies between plants and animals might help in the explanation of plant reproduction. Theophrastus is well aware that the analogy here does not help very much in this case, and his examination of the ways in which his predecessors have thought that plants can propagate ‘spontaneously’ is widely cited today as an example of how his insistence on close observation of even difficult phenomena leads him to criticize the assumptions of earlier theory. His ultimate view is that spontaneous generation is possible in both some animals, and in plants – this is the received view, and the view of Aristotle. Yet after stating the received view, Theophrastus characteristically proceeds to underline its flaws; in many cases, what we might think to be the result of spontaneous generation could just as easily have reproduced in a less unusual way through the transport of seeds through the air, or by water, or it could be that these plants do in fact have seeds, but that they escape our notice in some way. (De causis plantarum, I, 5). Without explicitly contradicting any earlier authorities, Theophrastus manages to make it clear that the subject requires further careful, practical study.

Compare the even more striking case of his analysis of the medical and magical properties of plants, in the Book IX of the Historia plantarum, where some quite extraordinary material is included, even when Theophrastus is highly suspicious of its veracity, because he clearly believes that a careful investigator should reasonably include such information where it exists. Theophrastus often remarks that the information he has collected has been gathered either in order to generate hypotheses, or by way of hypothesis (Historia plantarum, II, 6, 11; IV, 13, 2; De causis plantarum, I, 2, 2). Strikingly, he is generally happy to leave the matter at that.

In short, Theophrastus’ catholic approach to collecting the differences, the diaphoraí, even when they seem unbelievable, even when he can tell that they are going to cause problems, is a particular hallmark of his method, and one which we may see as a perfectly logical extension of what we find in Aristotle himself. It seems clear, to judge from Theophrastus’ own work, that his research did not ever place him in a position of fundamental disagreement with Aristotelian scientific method. And this aspect of his research continued long after his death, shorn of its cautious side and its ultimate commitment to explanation, in the ancient tradition of Mirabilia, of collecting outlandish and extraordinary pieces of information. Along with the doxographical tradition, about which more will be said below, the ancient scientific interest in Mirabilia is often traced back to Theophrastus.

Strato took over the Headship of the Lyceum after Theophrastus, and occupied the position for around eighteen years, between 286 and 268. Unlike Theophrastus, none of his work survives through its own independent tradition; for Strato, as with all his successors at the Lyceum, we are entirely dependent on the indirect tradition, on quotations preserved by other writers. The quality of some of this testimony is questionable in the extreme.

Strato was associated in antiquity with a particular interest in physics (he is often given the nickname Physikós), and he is thought to have provided Hero of Alexandria with much of the theoretical material that appears in the introduction to Hero’s Pneumatica. Yet Strato is nowhere mentioned by name in any of Hero’s surviving works, and the evidence for his presence in Hero, though widely accepted, is circumstantial at best. The strongest evidence comes perhaps from the fact that one quotation which the sixth-century commentator Simplicius attributes specifically to Strato, also occurs, without any attribution, in Hero’s Pneumatica. Cicero reports that the Peripatetic school began its long decline with Strato, whose particular interest in physics was, he claims, pursued at the expense of other matters (notably in ethics and logic) which Aristotle and Theophrastus had regarded as equally important. Some ancient witnesses report that he taught Ptolemy Philadelphus and received a huge fee for doing so; if this is true, it would certainly fit well with the later evidence which suggests that Peripatetic philosophers and methods were prominent in the early years of the Museum at Alexandria.

The list of Strato’s works preserved by Diogenes, whilst a good deal shorter than those associated with Aristotle himself and Theophrastus, does not really substantiate this charge of narrowness or specialisation; his works included treatises on ethics, political and constitutional theory, animals, perception and logic, along with a work On the void, in which he presumably set out the ideas for which he is today best known.

Diogenes either knew or cared little about Strato’s scientific work. In the case of his other biographical subjects, Diogenes is happy to become involved in philosophical detail; but he says hardly anything about Strato beyond recording a document which he claims to have been the man’s will, and telling us that when he died, he was so emaciated that he felt no pain. Strato is a more important figure today, mainly because of his criticisms of Aristotle’s views on the nature of space, void and place. And these criticisms are doubly interesting for us, because they cast light on the nature of Strato’s status as a Peripatetic, as much as on the problems in Aristotelian physics at which they are targeted.

Aristotle himself was committed to the view that void could not exist within the cosmos in any sense other than as a three-dimensionally extended space which is always actually occupied by body. Plato had taken a broadly similar line, and throughout antiquity there is a more or less clear division between those who believe matter to be continuous, and those who believe that without space absolutely empty of matter, motion and change cannot be possible. The latter position is, of course, the position of the atomists, including Democritus and Epicurus. Strato’s striking contribution to the debate was to argue that void could in fact exist within this cosmos, as space in the interstices between ill-fitting particles of matter. This, he seems to have called ‘small-void’. Larger-scale void, he apparently argued, can also exist, but only when it is created by unnatural force. On this argument, the ‘inert void’ of the atomists becomes ‘vacuum’; either Strato himself or those associated with him seem to have developed the idea that «nature abhors a vacuum».

The importance of this principle in explaining a large number of physical phenomena was quickly recognized, and it seems very likely that elements of Stratonic physics underpin the physiological theory of the doctor Erasistratus of Cos. Erasistratus (himself, according to some ancient witnesses, a pupil of Theophrastus) had made use of a principle he called «movement towards what has been evacuated» to explain how the motion of fluids within the body can give rise to various consequences. For example, it seems that he explained respiration in terms of the natural tendency of the lungs, when opened like a bellows, to draw in air from outside, through the windpipe. It seems likely that Erasistratus spent a good part of his life working in Alexandria, and this particular example, poorly documented though it is, raises interesting questions about the nature of relations between the Lyceum at Athens and the Museum at Alexandria in the late fourth and early third centuries BC.

If the modern attribution of Hero of Alexander’s pneumatic physics to Strato is correct, then we have in the Pneumatica an extended example of the practical applications of Strato’s research, to the construction and explanation of toys and machines driven by the power of air and water. But as far as Strato’s character as a Peripatetic goes, the problem is a little more complex. There is no doubt that Strato’s acceptance of the possibility of void within the universe does not make him an atomic theorist; it does not move him decisively out of the Aristotelian continuum theorist camp. What it does suggest, though, is the same kind of independent mind, set on collecting and accounting for the physical phenomena above all else, which we have seen already in Theophrastus. No one would claim, of course, that Strato’s work, any more than Theophrastus’, is theory-transparent. Simply that it appears – on the scant evidence available – to have been open-ended and not bound by any Peripatetic orthodoxy.

In the generations after Theophrastus and Strato, prominent members of the School seem to have pursued increasingly narrow, divergent interests, and at times in highly independent ways. Figures like Heraclides of Pontus, for instance, although they are included in the standard modern edition of fragments of early Peripatetics, are difficult to characterize as strictly Aristotelian because of their long-standing connections with the Academy. (Heraclides, for instance, is mentioned in the ancient Academicorum index). Ambition for the top job as Scholarch might have encouraged some degree of ‘loyalty’ towards the memory of the School’s founder, but it is important to remember that teachers as much as pupils rarely felt bound to one particular school; and pupils themselves moved from institution to institution with some frequency, sampling what seemed to them rewarding – the experience of the young Cicero studying in Athens is a case in point. The question of determining who should be included in the list of later Aristotelians is further hampered by the fact that the Lyceum never really existed to proselytize Aristotelian doctrines; members came and went, and in particular there was a good deal of interchange between the Peripatos and the Academy in the early years.

What is more, it seems clear that the concept of the philosophical school, and what made its members worthy of its name, changed over time. When figures like Cicero and Simplicius criticize ‘Peripatetics’ of their own day for ignoring the doctrines of their founder, they were assuming a degree of sectarian loyalty which may not have existed even amongst the earliest Peripatetics. It is a type of loyalty which the restoration of philosophical schools at the end of the second century AD seems to have encouraged rather artificially. Alexander of Aphrodisias, for instance, was appointed a public interpreter of Aristotelian philosophy around 200 AD, and composed a number of highly influential commentaries, all of which tend to explain Aristotle on his own terms, rather than employ new and different philosophical techniques and discoveries to criticize and build on his thought. It is surely significant that the most important ancient commentators on Aristotelian natural science, Philoponus and Simplicius, were neither of them Aristotelian.

In fact, most of the philosophical schools had come to take on the character of proselytizers of entrenched positions as early as the first century BC; where a basically sympathetic observer like the Academic Cicero often sees little between them, in the second century AD, the satirist Lucian can pit a Peripatetic and an Academic against each other, each arguing the merits of his own philosophical system (Piscator, 43, 4). Indeed, the frequency with which Lucian satirizes school philosophers suggests that they were seen in some sense as “fair game” by the educated public at large.

The list of early thinkers regarded as thorough-going Peripatetics, then, is a relatively short one and appears here as little more than an appendix. Dicaearchus of Messene, for instance, a contemporary of Theophrastus and a pupil of Aristotle, wrote on a variety of subjects, in the main ethical and political rather than scientific. We know of him mainly because he disagreed with both Aristotle and Theophrastus on the nature of the soul, arguing that it has no existence outside the physical nature of the animal itself. This, on the face of it, is an important divergence from Peripatetic doctrine and brings Dicaearchus into the company of the atomists and Epicureans, although in other significant respects – for example in his belief that the Earth is spherical – he followed Aristotle more conventionally. This type of independence at the level of detail is typical of many later Peripatetic philosophers and calls to mind what we have already seen in the case of Strato. He was also known in antiquity as the author of a practical geographical work (now lost), which apparently included calculations of the heights of the major Greek mountain ranges and attempted a geometrical division of the world.

Demetrius of Phaleron, a pupil of Theophrastus, seems to have moved to Alexandria, and brought Peripatetic research methods to the Alexandrian Library. Diogenes Laertius reports, as we have already noted, that Strato taught Ptolemy Philadelphus; whatever the truth of this report, it certainly would appear that Peripatetics of the third century were closely involved in the establishment of the Museum and Library in the Brucheion at Alexandria. Clearchus of Cyprus, another pupil, apparently pursued ethnographical researches, in addition to writing a work in praise of Plato, and a set of comments on mathematical problems posed by certain passages in the Republic. Reports such as this one suggest that relations between Peripatetics and members of the Academy were complex, and far from hostile. In the De finibus, Cicero, for instance, frequently draws little distinction between the two groups. But if scientific interests are typical of the early Peripatos – Clearchus apparently composed a work On bodies, which apparently contained an anatomical commentary on the skeleton and muscles of man – this was by no means always the case. By the first century BC, the concern with natural science had become the particular province of the Stoics, and figures like Posidonius of Apamea in particular.

The most famous ancient student of harmonic theory, Aristoxenus of Tarentum spent some time, it seems, studying in Plato’s Academy before joining the Lyceum (the Suda records that he also studied with a Pythagorean called Xenophilus). Aristoxenus is supposed to have fallen out with the Lyceum on Theophrastus’ appointment as its head. Ancient witnesses testify to Aristoxenus’ rather combative character, and he makes frequent claims in the Harmonics to be the first person ever to have tackled the subject of musical theory properly. ‘Properly’ in the context turns out not to be in the manner of the most influential early students of the harmonics, the Pythagoreans, who sought in certain musical intervals proof of the importance of number in the constitution of the world (the Socrates of Plato’s Republic seems to come from the same kind of tradition, when he advocates the study of harmonics without resorting to the torturing of strings and pegs). Aristoxenus insists that his subject can only be studied by the careful collection of the phenomena, and their subsequent examination according to the canons of Aristotelian scientific logic; that his own intellectual affiliations were complex may be surmised from the fact of his having written a life of his compatriot Pythagorean Archytas which seems not, to judge from the surviving fragments, to have been wholly polemical.

The Lyceum was also responsible for more than the dissemination of a scientific method, and a succession of individuals. There is a good deal of evidence, direct and circumstantial, to link the Peripatos from its earliest days to the ancient doxographical tradition – the tradition of recording the important doctrines of various authorities in natural science and mathematics. Aristotle himself had his own reasons for taking an interest in the opinions of earlier authorities. In the case of any problem he faced, the basic phenomena which had to be accounted for included wherever possible the views of earlier thinkers. Several of Aristotle’s most important works – for instance Metaphysica, De generatione et corruptione and De anima – begin with detailed summaries of the doctrines of his predecessors. We are told by the ancient biographers that Aristotle actually composed monographs on some of these predecessors, notably Democritus, not for the purpose of creating a historical record so much as to gather all the information necessary for new attempts at old problems.

Theophrastus shared Aristotle’s conception of the importance of this kind of information in the early stages of research. His short work on the physiology and philosophy of perception, the De sensu (On perception) shows him clearly at work in this tradition, gathering pre-Aristotelian explanations of the phenomena of sight, taste, hearing and so on, as a prelude to his own investigations. An interest in collecting the éndoxa – as Aristotle called the opinions of earlier wise men – alongside the sensible phenomena, rapidly became a characteristic of Peripatetic research, and many Aristotelians made it their business to write brief summaries of the history of their subjects.

Take the case of Eudemus of Rhodes (late fourth century BC), for instance. He had been disappointed by an unsuccessful bid to follow Aristotle as Head of the Lyceum, Eudemus seems to have remained a loyal follower of Aristotle’s teaching. So loyal in fact that some critics have accused him of producing little more than a rigid simplification of Aristotelian doctrines. In the absence of very much evidence – none of his work survives outside quotations in other authors – it is hard to judge the fairness of this criticism (he is especially associated by Simplicius in his commentary on the Physics of Aristotle with the support he gives the Aristotelian arguments against the Eleatics). Eudemus is best known today, however, as the author of a doxographical history of mathematics, part of which is thought to be preserved in Proclus’ In primum Euclidis elementorum librum commentarii. In his own classification of the sciences, Aristotle had drawn a distinction between physics – the study of body and the motions of bodies – and mathematics, which involved the abstract investigation of number and shape. He had himself offered a brief history of physics in the Book I of his own Metaphysics, in which the doctrines of his predecessors are set up for ultimate refutation; Eudemus’ mathematical work, if we are justified in judging it by what we find in Proclus, was much more discursive, offering little more than a list of names and the briefest of summaries of their doctrines.

Of a mysterious character called Menon, rather less is known. In his In Hippocratis de natura hominis commentarii (K XV 25), the doctor Galen offers us all we can really hope to learn about him: «if you wish to investigate the doctrines of the ancient doctors, then you can read the treatise on medicine, written in agreement with Aristotle and with his approval, by Menon, who was a pupil of his». Menon’s work was assumed to have been lost, until Hermann Diels argued in the late nineteenth century that the early sections of a medical papyrus in the British Museum bear a close similarity to Galen’s description of Menon’s History of medicine. The papyrus caused something of a stir when it was published, because it purported to record the actual medical theory of the historical Hippocrates. The controversy it generated has yet to subside.

Finally, and most importantly, Diels also demonstrated that several later encyclopaedic summaries of the work of natural scientists and their doctrines – for instance those contained in the Pseudo-Galenic History of philosophy and Pseudo-Plutarch’s Placita philosophorum contain material which probably has an ultimate source in a lost work on the Physikaì dóxai by Theophrastus. These general summaries of scientific and philosophical doctrines played, it seems, an important part in later antiquity in the disputes between thinkers of various methodological persuasions which are typical of Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman philosophy and medicine. Sceptical philosophers, for instance, made free use of the doxographies available to them, and the disagreements they illustrated, to underline the futility of theorizing about intractable problems. But even dogmatic theorists found the collections useful starting points in the rhetorical defence of their own positions.

By the time of Galen, in the second century AD, the doctrinal summary of early views had become a standard feature of many theoretical medical works. In ethics the case was similar; here a work on the history of the subject by the Peripatetic Arius Didymus was especially influential. If Diels’ hypothesis about the role of Theophrastus in preserving the thought and doctrines of his predecessors is true – and most modern scholars believe that it is – it means that without the Peripatetic tradition, our knowledge of early Greek philosophy would be negligible. Of course, the ancient motivations behind this kind of activity are altogether more complex. If Aristotle (and to a lesser extent, Theophrastus) had initially made it their business to gather the doctrines of their predecessors as a prelude to refuting or adjusting them, the doxographical tradition in later antiquity became an important vehicle for establishing and perpetuating the authority of certain lines of philosophical teaching.

It would be a mistake, then, to say that the influence of the Lyceum on the study of natural science in antiquity was either antiquarian, or simply promulgated through the few individuals named in the present discussion. And it would be a serious mistake to imagine that Aristotelian ideas exercised little influence on the history of Greek philosophy in the two centuries following Aristotle’s death; quite the contrary is the case. We must, of course, distinguish between the task of examining the history of Aristotle’s own school and that of examining the influence of Aristotelian thought on subsequent work in natural science and medicine. But because influence is, in intellectual as much as social and political contexts, just as likely to be negative as positive, tracing this side of the history is a complex task. Historians of philosophy point to the ultimately Aristotelian stamp on systems as various as Stoicism, for example, or Galenic physiology and Ptolemaic astronomy.

The influence of Aristotle’s School on intellectual life in early Alexandria has been the subject of much attention this century. It should be said, though, that the identity of members of particular philosophical schools seems to have been lost in the intellectual ecumenism of Alexandria, and there is little to lead us imagine that Aristotelian philosophy per se was taught or studied as a special, discrete subject there. And although there is not always a clear distinction drawn, especially in later antiquity, between the doctrines of the Platonic Academy and those of Aristotle, certain fundamental Aristotelian ideas are reflected even in Neoplatonism; some of the most important Aristotelian commentators of late antiquity, such as Simplicius, were themselves Platonists. Doctrines, for example, such as those relating to the character of purpose directed activity in nature, or the proofs of the Earth’s sphericity, or the idea that all matter within the universe is continuous or the basic antithesis between form and matter recur in many contexts where their origin is never acknowledged.

The most obvious, direct influence of Aristotelian philosophy was on the development of new schools of thought, most conspicuously the development of Stoicism on one hand, and on the other hand, Epicureanism. Even though both Aristotelians (including Strato), and Stoics were continuum theorists – denying the existence of void as the logical opposite of matter within the Universe – the two groups are distinguished by most of our later witnesses for their different logical systems, their divergent approaches to the problems of determinism and fate, and by the uniquely Stoic doctrine of the pneúma as the cohesive force which binds the world together.

The case with Epicureans is more striking, though, and given that the atomist hypothesis was absolutely opposed to all Peripatetic thinking, it is worth developing here for a moment. The Epicureans disagreed fundamentally with the whole Aristotelian world view, but even so, the stamp of Aristotle can be seen much more clearly in the Epicurean arguments deployed against the thesis that matter can be infinitely divided, than in many of the doctrines of Aristotle’s own so-called followers. At the beginning of Aristotle’s treatise De generatione et corruptione, there is a telling attack on the Democritean concept that matter can be divided to some finite limit, beyond which division is impossible. The product of this ultimate division, for the Democriteans, was the atom, something which could not be divided further on account of its «absolute solidity».

Aristotle argued that magnitudes can only be composed out of other magnitudes; if atoms are magnitudes – and indeed they must be, if the phenomenal world is to be composed of them – then there is no reason to suppose that they are not themselves further divisible into yet smaller magnitudes. For atoms cannot simply be points – nothing physical can be made out of insubstantial points. Without any explicit acknowledgment of this criticism – Epicurus’ own philosophical criticism is directed mainly at Democritus – Epicurus seems to have invented his theory of minimal parts, which allows individual atoms and their parts to be named, without this entailing the possibility of division through these parts. One gets the impression that Aristotle’s criticism actually strengthened the claims of the Epicureans – in their own minds at least – that they possessed in atomism an incontrovertible hypothesis.

A second type of intellectual association with Aristotle may be seen in medicine. Peripatetic influence on Hellenistic medical theory has long been studied; that it should exist is not in itself surprising. In the fourth and third centuries BC, Peripatetic methods and ideas dominated the philosophical life of the most important medical centre in the Greek world, Alexandria (so much so that some ancient sources seem to use the terms ‘Alexandrian’ and ‘Peripatetic’ interchangeably). Werner Jaeger argued at the beginning of XXth century that the doctor Diocles of Carystus had been influenced by Aristotle, and Peripatetic doctrines have already been noticed in the physiological theory of Erasistratus of Cos.

Of course the idea of tracing influence like this in the absence of reliable contemporary evidence is fraught with danger; and apart from anything else, we should not simply assume that Aristotle or the Aristotelians are the source of any ideas in others which are in harmony with their own. Far less should we allow our own suppositions about chronologically based networks of doctrinal transmission to determine the presence of supposedly Aristotelian notions in the work of others. One case does, though, call for attention. The Anonymus Londinensis reports that Herophilus coined an odd slogan, «let the phenomena be enumerated first, even if they are not first». This has carried a decidedly Aristotelian ring for most modern observers, who point out that in his insistence that the particulars on any subject, especially in natural science, should be collected before any conclusions are drawn, Aristotle was marking out his position from that of others, notably Plato, who took the very different view that the particulars thrown up by the evidence of our senses tend, as often as not, to confuse and distract us from the truth.

If Herophilus did indeed mean by his slogan that the collection and appraisal of the perceptible phenomena must form the first stage of a scientific investigation, then he is placing himself in very much an Aristotelian light, and similarly placing his whole Alexandrian milieu. Stronger, if rather more circumstantial evidence comes from the increased interest in dissection – including human vivisection – which is associated by some ancient witnesses with the names of Herophilus and Erasistratus; it seems very likely that such kinds of investigation were made possible by the kind of shift in attitude towards the autoptic study of anatomy which we can see in the Book I of Aristotle’s De partibus animalium.

It should be clear by now that the term ‘school’ in the context of the early Lyceum is something of a misnomer. Our picture of the Lyceum suggests a loosely organized institution in which a variety of people undertook research in a wide variety of areas, sometimes adopting little that was strictly based on explicit Aristotelian doctrine beyond the epistemological freedom which came from the idea that the study of phenomenal particulars should be given precedence in the early stages of an investigation. The Lyceum, as we have seen, persisted for a relatively short time in its original form, compared to an institution like the Academy. Even in its early days in Athens, the inner circle of Peripatetics appears as a loosely knit ‘family’ of people who shared a similar kind of open-ended interest in the world. It seems that pupils came and went. There is little sign of any impulse towards the active promulgation of Aristotelian doctrines, let alone the dissemination of his writings until well into our own era, when the establishment of formal sectarian philosophical schools by the Antonine Emperors paved the way for the development of Aristotelian scholasticism.

The lack of intellectual agreement on precise matters of doctrine among the early Peripatetics – on the nature of void, in the case of Strato, for example, or the status of fire as an element for Theophrastus – does not suggest that the Aristotelian philosophy itself lacked strength. Quite the contrary, in fact. Aristotle’s own surviving works show the same kind of developing understanding of particular problems which can be seen in the work of the generations immediately following him. No wonder, perhaps, that Simplicius, writing in a quite different intellectual context in the sixth century AD, was surprised by the audaciousness of Strato for attacking the Aristotelian doctrine on void; «even though he was himself a pupil of Theophrastus and followed Aristotle in almost all things, here he followed a rather strange path of his own». In any case, disagreement was a fact of life in nearly all Greek intellectual institutions, with the possible exception of Epicureanism which rapidly seems to have assumed the status of something like a religion. The agonistic nature of Greek intellectual life generally meant that pupils did feel able to criticize their teachers - in the case of figures like Epicurus, the harshest criticism was reserved for men like Democritus to whom his debt was greatest.

Aristotelianism did not, in antiquity, seek to offer the kinds of certainty provided by Platonism and Neoplatonism. Certainty has its attractions, of course, and the Academy was still flourishing in Athens in the fifth and sixth centuries AD, in the company of the likes of Proclus and Simplicius. Similarly, Epicureanism persisted as its disciples, from Lucretius onward, sought to transmit unchanged the doctrines of their founder. The Emperor Marcus Aurelius was a Stoic. By its very nature, Aristotelian science was flexible, and did not carry with it a creed; although there were definite matters upon which Aristotelians agreed – such as the sphericity of the Earth, the presence of design in nature, the lack of large scale void, and a dynamic theory predicated on the superiority of centrifocal motion – in the end it was a method, and not a set of answers to problems.

For a time, the School of Aristotle dissolved into the intellectual bloodstream of Graeco-Roman natural science. When it was resuscitated in later antiquity, the temper of that age sought answers more than methods.

John Vallance

References

- Barker 1991: Barker, Andrew D., ‘Aristoxenus’ harmonics and Aristotle’s theory of science, in: Science and philosophy in classical Greece, edited with a preface by Alan C. Bowen, New York, Garland, 1991, pp. 188-226.

- Diels 1903: Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, griechisch und deutsch, hrsg. von Hermann Diels, Berlin, Weidmann, 1903 (6. ed.: hrsg. von Walther Kranz, Berlin, Weidmann, 1951, 3 v., spesso indicata con la sigla DK).

- Frede 1992: Frede, Michael, Doxographie, historiographie philosophique et historiographie historique de la philosophie, Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale, 3, 1992, pp. 311-326.

- Furley 1989: Furley, David J., Strato’s theory of the void, in: Furley, David J., Cosmic problems. Essays on Greek and Roman philosophy of nature, Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press, 1989, pp. 149-160.

- Gigante 1997: Gigante, Marcello, La scuola di Aristotele, in: Beiträge zur antiken Philosophie. Festschrift für Wolfgang Kullmann, hrsg. von Hans-Christian Günther und Antonios Rengakos, Stuttgart, F. Steiner, 1997, pp. 255-270.

- Lloyd 1968: Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard, Aristotle. The growth and structure of his thought, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1968.

- — 1987: Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard, The revolutions of wisdom. Studies in the claims and practice of ancient Greek science, Berkeley (Calif.), University of California Press, 1987.

- — 1991: Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard, Aristotle’s zoology and his metaphysics: the status quaestionis, in: Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard, Methods and problems in Greek science, Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 372-397.

- Lynch 1972: Lynch, John Patrick, Aristotle’s school. A study of a Greek educational institution, Berkeley (Calif.), University of California Press, 1972.

- McDiarmid 1953: McDiarmid, J.B., Theophrastus on the presocratic causes, Harvard studies in classical philology, 61, 1953, pp. 85-156.

- Ostwald 1977-94: Ostwald, Martin - Lynch, John P., Greek culture and science. The growth of schools and the advance of knowledge, in: The Cambridge ancient history, edited by Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards [et al.], Cambridge; New York, Cambridge University Press, 1977-1994, 6 v.; v. VI: The fourth century, edited by D.M. Lewis [et al.].

- von Staden 1989: Staden, Heinrich von, Herophilus. The art of medicine in early Alexandria, Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Vallance 1988: Vallance, J.T., Theophrastus and the study of the intractable, in: Theophrastean studies. On natural science, physics and metaphysics, ethics, religion, and rhetoric, edited by William W. Fortenbaugh and Robert W. Sharples, New Brunswick, Transaction Books, 1988, pp. 25-40.

- Wiesner 1985: Aristoteles, Werk und Wirkung. Paul Moraux gewidmet, hrsg. von Jürgen Wiesner, Berlin-New York, W. de Gruyter, 1985-1987, 2 v.; v. I: Aristoteles und seine Schule.